I've reserved a review copy of the forthcoming

Foxit eSlick, Foxit software's horribly-named e-book reader due out next month. It's not new technology, but at $229, this could be the first reader that lots of people actually buy. It also will read pdf's, unlike the abominably proprietary Kindle [note: I've been informed, in the comments, that there is indeed a way to read pdf's on the Kindle, sorry], which is what interests me about it, as I read a lot of manuscripts that are thrown out immediately afterward, and which I'm not interested in reading on a computer screen.

Now, I'm not terribly interested in one of those real-books-versus-e-books aesthetic debates. Yes, we all love the feel of a book in our hands, the discolored paper, the marginal notes blah blah blah blah. Doubtless there will be room in the world for both formats, and nobody alive today is likely to ever see book-lined rooms obliterated from existence. So chill.

But I am interested in the other possible consequences of this technology. So far, writers don't seem to have suffered much from the possibility of cracked copyrighted content, probably because they don't make much money to begin with, and mostly because not many people read literature in this format. But once the practice is widespread (as I've said before, I think it will be, once we have inexpensive readers that look half decent), piracy will probably be widespread as well, and literature might well go the way of music, with a vast percentage of people culturally acclimated to the idea that it is, in effect, free.

There are a few problems with this analogy, though. One is that musicians, at the dawn of file sharing, were already not making much money off of records. The money comes from touring. This trend has been hugely amplified in the wake of Napster, etc., and now many musicians and record companies have come around to

also thinking that recorded music is basically free. The moral calculus involved in stealing music has changed, and most music acts don't even consider records a major source of revenue anymore. This doesn't make music piracy OK, of course, but it is now lower in the heirarchy of sins than, say software piracy. (For an interesting read on that subject, check out

this Analog Industries post.)

This is bad news for writers, because we make no money from touring. Indeed, at least in the short run, publishers lose money on touring. For one thing, literary readings are generally free. Second, fans of writers don't really need to hear them read. If you love Bruce Springsteen, you are going to buy Springsteen tickets, because much of the pleasure in his music comes from the concept of its spontaneous creation; furthermore, when you go to a concert, you are hearing something unique, not just a rehashing of the record. In a concert, the music is being created

now. But if you love, say, T. C. Boyle, you really don't necessarily want to hear him read. You might like to see what he's like in person, but ultimately, it's just going to be a guy reading out of a book, the same book you already read. Literature is cerebral, not physical and extemporaneous. The action all happens offstage; a book is merely its ultimate result. A reading is nice, but it isn't the act of creation. It's a shadow on the wall.

However, there's another problem with the e-book/mp3 analogy, and that is that literature is

already free. Indeed, anyone in America can read any book he or she wants. All you have to do is go to your free public library, get a free library card, and check it out. You might have to pay fifty cents for an interlibrary loan. The main reason to buy a new book is that you want it

now. (You might also suspect it will have lasting value, and you'll want to read it again.) But ultimately, very few writers make any money off of their books.

Now, I am talking here about Literature. The vast number of books that sell are not fiction or poetry--they're reference, cookbooks, celebrity memoirs, etc., and these books

do make money. But for most of us, piracy is not very worrisome. Who the hell is going to steal my book? most literary writers would say, hardly anyone wants to read it to begin with.

This technology could be great for small-time writers who might want to sell novels, say, off their websites for five bucks, the way a lot of independent bands do with their records. But of course the public has to know, and care, that you exist to begin with. Bands achieve this by touring. And I bet a lot of writers would, too, if they could. Unless you're on the self-help lecture circuit, though, you really can't. Nobody will care, because like I said, it's not the physical presence of bands that pack clubs, it's the spontaneous creation of a work of art. And nobody ever danced to Jonathan Safran Foer.

Many of us who are into contemporary music could see the record industry crisis coming from a thousand miles away. Record execs blew it in slow motion, with their reluctance to embrace downloading and create subscription services. Instead they waited too long and tried to shove the genie back in the bottle with lawsuits and DRM. They were "right" to do those things, but it was never going to work.

I can't see the future of publishing, though. Maybe, ultimately, e-books will just not take off the way digital music has. Maybe digital will always be the ugly stepchild of print. In any event, here's my wild prediction: ten years from now, all the best literary writers will be at small presses, who will put out short-run print editions at a premium, while offering direct downloads at a heavily discounted price. And we will all go from not making much money to making almost no money, and we'll all sigh ruefully and accept it.

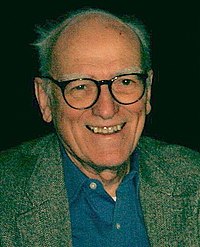

Alas, dead at 76. I never loved his novels, but I've read and re-read the Henry Bech stories with great enjoyment, and have long been a fan of the essays and reviews. I honestly have no idea what history will have to say about him; I suspect he'll be remembered as the author of the Rabbit Angstrom books. I don't know how well these will age--perhaps not that well. (I'm accustomed to this being a minority opinion.) But his short stories, I hope, especially the early ones, may rally, and come to form his legacy. The best book about him, on the other hand, is easy: Nicholson Baker's hilarious U and I.

Alas, dead at 76. I never loved his novels, but I've read and re-read the Henry Bech stories with great enjoyment, and have long been a fan of the essays and reviews. I honestly have no idea what history will have to say about him; I suspect he'll be remembered as the author of the Rabbit Angstrom books. I don't know how well these will age--perhaps not that well. (I'm accustomed to this being a minority opinion.) But his short stories, I hope, especially the early ones, may rally, and come to form his legacy. The best book about him, on the other hand, is easy: Nicholson Baker's hilarious U and I.